Shoulder Anatomy

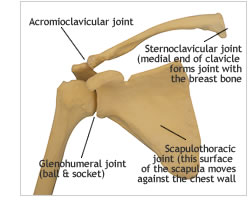

The shoulder is one of the most complex joints in the body and is formed by the confluence of 3 bones (humerus, scapula and clavicle) Fig. 1a and 1b. These together form what is called the shoulder girdle.

The shoulder girdle provides a stable platform for function of the arm and hand, it has a number of unique features:

- The shoulder girdle consists of 5 ‘joints’ i.e. sternoclavicular joint, acromioclavicular joint, scapulothoracic joint, the subacromial ‘joint’ and the glenohumeral joint (true shoulder joint; ball and socket) Fig. 2a and 2b.

- The glenohumeral joint has the greatest range of movement of any joint in the body thus allowing the hand to be placed in a multitude of different positions.

- This extensive range of movement does mean that it is the most unstable joint and thus the joint most prone and common to dislocate.

- It depends on soft tissue structures (tendons, labrum and ligaments) around it for stability and for control of the finer movements. Pathology and injury of these soft tissue structures are the most common reason for problems in the shoulder.

Would you like to see a doctor?

Learn more

Bones of the Shoulder

Bones of the Shoulder (Fig 1a and 1b)

The clavicle or collar bone forms a link between the sternum (breast bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade).

The scapula or shoulder blade lies over the ribs at the back of the chest.

The glenoid (socket) is the part of the scapula that forms a joint (glenohumeral joint; ball and socket) with the head or ball of the humerus (arm bone).

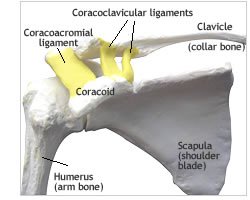

The acromion is part of the scapula that projects above the humeral head forming a shelf or roof.

The coracoid is part of the shoulder blade that projects in front of the glenohumeral joint (ball and socket); it is important in that it is the point of attachment of the ligaments that connect the clavicle (collar bone) to the scapula (shoulder blade). One of the tendons of the biceps muscle is attached to the tip of the coracoid. This is the bone that is transferred to the front of the socket in the Latarjet operation for a dislocating shoulder.

The humerus or arm bone is the connection between the shoulder and the elbow.

The head (ball) of the humerus forms a joint (glenohumeral joint) with the glenoid (socket) of the shoulder blade.

Joints of the Shoulder Girdle

The shoulder girdle consists of 5 joints:

Sternoclavicular joint – one end of the clavicle (collar bone) forms a joint with the sternum or breast bone.

Acromioclavicular joint – the other end of the clavicle (collar bone) forms a joint with the acromion (part of the shoulder blade which forms a roof or shelf above the humeral head or ball).

Glenohumeral joint – the head of the humerus (ball) moves against the socket (glenoid). However unlike the hip joint where the ball fits into the socket, the ball is held against the socket.

Scapulothoracic joint – the shoulder blade moves against the chest wall, this joint is responsible for approx 1/3 of the movement of lifting the arm above the head.

‘Subacromial joint’ – this is not a true joint but is where the rotator cuff tendons move against the undersurface of the acromion. The subacromial bursa is a sac between the undersurface of the acromion and the rotator cuff tendons. When injecting for rotator cuff problems, the doctor injects the fluid into the bursa.

Capsule, Labrum and Ligaments

Capsule, Labrum and Ligaments (Fig. 3a, 3b, 3c and 3d)

All joints are enclosed in a capsule or sac (Fig. 3a) in which there is fluid which lubricates the joint. The capsule of the glenohumeral joint is extremely loose allowing an extensive range of movement.

The labrum (Fig. 3b) is a rim of tissue which is attached around the edge of the socket; it is triangular in shape on cross section and thus deepens the socket helping to make the ball and socket joint more stable. It is this tissue which is torn off the socket when the shoulder dislocates.

Ligaments are tough soft tissue structures that connect different bones together.

The gelnohumeral ligaments (Fig. 3c) are thickenings of the capsule at the front of the shoulder connecting th ball to the socket and contribute to the glenohumeral joint’s stability.

The coracoacromial ligament (Fig. 3d) extends between the acromion and coracoid and completes the shelf or roof (coracoacromial arch) above the humeral head (ball). Thickening of this ligament may cause the rotator cuff tendons to catch or impinge against it causing shoulder pain.

The coracoclavicular ligaments (Fig. 3d) of which there are two, connect the clavicle to the scapula and are torn in a complete dislocation of the acromioclavicular joint.

Tendons and Muscles

Tendons and Muscles

A tendon is part of the muscle which attaches to bone. Tendon is a tough, non elastic soft tissue structure whereas the muscle is soft and elastic which contracts and relaxes thus causing movement.

The Rotator Cuff Muscles and Tendons (Fig. 4a,4b and 4c)

The rotator cuff consists of 4 muscles and their tendons:

1. SUBSCAPULARIS (at the front)

2. SUPRASPINATUS (at the top)

3. INFRASPINATUS (at the back)

4. TERES MINOR (at the back)

These muscles are attached to the scapula (shoulder blade); from the scapula the supraspinatus, infraspinatus and teres minor pass under the acromion and attach around the head or ball of the humerus via their tendons.

The subscapularis muscle passes under the coracoid at the front of the shoulder attaching via it’s tendon to the front of the humeral head or ball.

The rotator cuff tendons form a ‘hood’ over the humeral head (ball) and keep the ball against the socket. They control the finer movements of the shoulder; initiating the lifting of the arm and rotation of the shoulder.

Overuse, normal wear and tear (degeneration) or rupture of one or more of these tendons are a common cause of shoulder pain.

Muscles and Tendons

Biceps Muscle and Tendons (Fig. 5)

The biceps muscle is attached to the shoulder with 2 tendons; the long head and short head. The long head is attached to the top of the glenoid (socket) and passes through the glenohumeral joint (ball and socket) then passes in a groove in the humerus and finally attaches to the biceps muscle. The short head is attached to the coracoid and joins the long head at the muscle. Tendinitis or tearing of the long head of biceps is a common cause of pain in the shoulder. The biceps tendon fairly commonly ruptures in older people leaving the biceps muscle looking all bunched up (‘popeye muscle’).

Deltoid (Fig. 6a and 6b)

This large muscle gives shape to the shoulder; it lifts the shoulder away from the body, flexes it forwards and extend is it backwards. The deltoid works in unison with the rotator cuff muscles; these hold the humeral head (ball) against the socket providing a dynamic fulcum so the deltoid can lift the arm up sideways.

Pectoralis Major (Fig. 6a)

This passes from the chest wall to the upper part of the humerus (arm bone); it gives support at the front of the shoulder, pulls the arm towards the body and turns the arm inwards.

Scapula Muscles (Fig. 6b)

These include the trapezius, levator scapula, rhomboids and the serratus anterior, These muscles stabilise and control the movements of the scapula (shoulder blade). Weakness or loss of function of these muscles lead to winging of the scapula.

Nerves of the Shoulder

Nerves of the Shoulder

The Brachial Plexus is a junction of nerves which passes under the clavicle (collar bone) through the axilla (arm pit) before forming the nerves that pass down the arm. The nerves pass signals from the brain to control the muscles and also carry impulses from the arm back to the brain which are responsible for feeling in the arm.

Nerves that control the shoulder arise from the brachial plexus and include:

Axillary nerve which supplies the deltoid muscle; this nerve may be damaged when the shoulder dislocates. This is usually just stretching of the nerve and most often recovers with time.

Musculocutaneous nerve supplies the muscles that bend the elbow (brachialis) and supinate (i.e. turn the forearm outwards) the forearm (biceps). This nerve is close to the front of the shoulder and is at risk in certain operations.

Nerve to Serratus Anterior (Long Thoracic Nerve) supplies the serratus anterior muscle which holds the scapula (shoulder blade) against the chest wall. It can be injured or affected by a viral infection. When this happens, the scapula or shoulder blade wings (i.e. sticks out).

Suprascapular nerve supplies 2 of the rotator cuff muscles and can be injured or entrapped in a groove it passes through at the top of the scapula (shoulder blade). This results in weakness of the shoulder and inability to lift the arm fully.

Surgery procedure

Shoulder Arthroscopy

Most surgical procedures of the shoulder are now performed with arthroscopy. This involves the inserting of a telescope (fibre optic) through a thin tube in small incisions around the shoulder. The incisions are between 0,5 to 1,0 cm in size and between 2 and 6 incisions are used depending what operation is done. A single stitch or suture is used to close the incisions after the operation.

This is less invasive but the operation inside is the same as those done with an open operation and thus recovery may still take months depending on the procedure performed.

ARTHROSCOPIC PUMP

To facilitate the arthroscopic (keyhole) surgery, fluid is pumped into the shoulder. This opens the spaces in the shoulder and prevents bleeding. During the procedure some fluid leaks into the tissues around the shoulder which can become very swollen. This fluid is absorbed over the following few hours and patients may find that they pass more urine during this period as this fluid is excreted. Some of this fluid which is blood stained leaks out the small incisions and an absorbent dressing (nappy) is strapped to the shoulder. This is left on overnight and is replaced with small waterproof dressings the next morning so that the patient can shower normally.

This bloody fluid tracks down between the skin layer and muscle and patients may develop quite marked bruising down their arm and over their chest/breast during the week following the operation. This bruising will disappear over 2 -3 weeks.

ANAESTHESIA

This is done with a general anaesthetic and a regional block. It can be done with a block alone but the patient is placed into a seated position on the operating table which can be uncomfortable and thus a general anaesthetic is preferred. The block is done with local anaesthetic injected into the side of the neck where the nerves to the arm are passing. This provides excellent pain relief during the operation thus less anaesthetic drugs are required, patients thus wake up quite refreshed afterwards. The block provides excellent relieve of pain after the operation and lasts for between 8 and 24 hours. The arm may be completely dead and the patient may not even be able to move their fingers initially. Care must be taken not to put anything hot on the arm as this will not be felt and a burn may occur. In approximately 1% of cases there may be a persisting area of numbness in the arm, forearm or hand which usually disappears within 3 months. Occasionally neuralgia (nerve pain) may occur after the block and may require medication till it settles of its own accord.

HOSPITAL STAY

Patients come in on the day of the operation and may be discharged a few hours after the operation or may stay overnight depending on the operation performed and how they are feeling.

MEDICATION

An anti-inflammatory and a pain killer are prescribed. The anti-inflammatory is taken for a week and the pain killer if and when necessary. Most patients take the pain killer for an average of 5 days after the operation. Some patients however don’t take any medication whereas other patients may need pain killers for up to 6 weeks. This is dependent on the individual and the operation performed. More pain is usually felt following a rotator cuff repair. Patients often struggle to sleep initially and a sleeping tablet may be required.

SLEEP

Patients often have difficulty sleeping and besides taking sleeping tablets, sleeping propped up with pillows or sleeping in a chair will be easier. A recliner (lazy boy chair) will often be the best option.

Anaesthesia

The anaesthetist will see you in the ward prior to the operation or in the reception room in theatre. If you have medical problems; eg: heart condition, previous cardiac surgery, chest disease (eg: emphysema), you will be referred to a physician for an assessment and may see the anaesthetist a few days prior to the operation. A premed is sometimes given prior to theatre which will make you a little drowsy and relaxed. In theatre you will sit on the theatre table and make yourself comfortable prior to the induction of anaesthesia. A drip will be inserted into your arm through which the anaesthetic drugs are administered. Gases will be given by a mask and once you are asleep a tube will be inserted into your throat, this is why you may have a sore throat for a short time after the operation.

The anesthetic is a general anaesthetic with a regional block. It can be done with a block alone but you are placed into a seated position on the operating table which can be uncomfortable and thus a general anaesthetic is preferred. The block is done with local anaesthetic injected into the side of the neck where the nerves to the arm are passing (essentially an epidural of the arm). This provides excellent pain relief during the operation thus less anaesthetic drugs are required; you tend to wake up quickly and are quite refreshed afterwards. The block provides excellent relieve of pain after the operation and lasts for between 8 and 24 hours. The arm may be completely dead and you may not even be able to move your fingers initially. Care must be taken not to put anything hot on the arm as this will not be felt and a burn may occur. In approximately 1% of cases there may be a persisting area of numbness in the arm, forearm or hand after the block has worn off. This numbness will usually disappear within 3 months. Occasionally neuralgia (nerve pain) may occur after the block and may require medication till it settles of its own accord. Although extremely rare, permanent nerve damage has been reported.

You tend to wake up very quickly after the operation and may eat soon afterwards. The drip will be taken down when you are back in the ward. The block provides excellent pain relief for between 8 and 24 hours but pain killers and anti-inflammatories are started before the block wears off so that they are already working when the pain starts. Patients vary in the amount of pain killers that they need; some don’t need to take any whereas others may need to take them for up to 6 weeks.