Elbow Anatomy

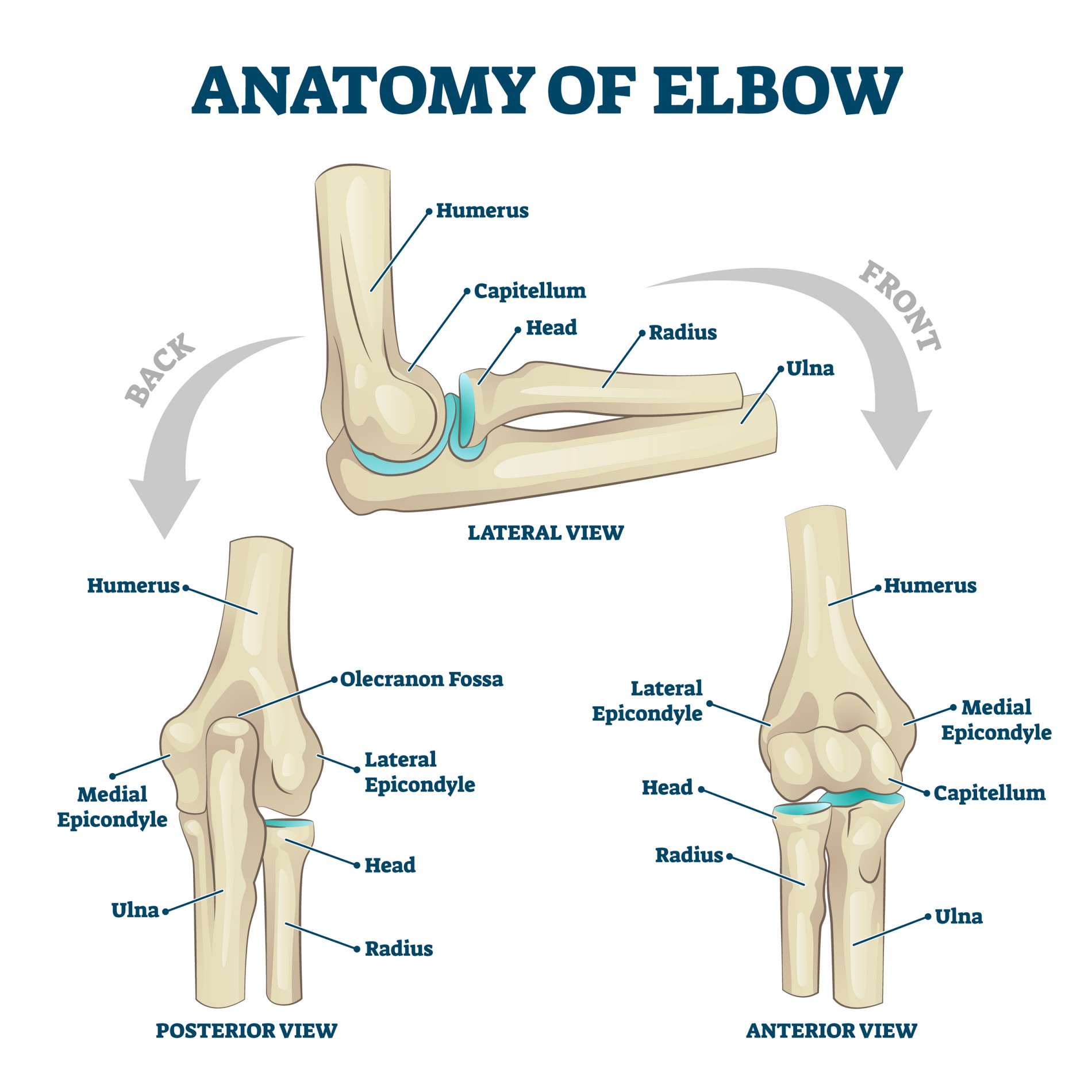

The elbow joint is the joint between the humerus (bone of the upper arm) and the radius and ulna (bones of the forearm). The movement across this joint is perceived to be a simple hinge joint but in fact there is far more complexity in the movement that takes place here.

The majority of the flexion and extension at the joint takes place between the upper end of the ulna (trochlea notch) and the lower end of the humerus (trochlea). The upper end of the radius (radial head) articulates with the capitellum on the lateral side (outside) of the joint. This articulation on the outside of the joint is less constrained and allows smooth flexion and extension. It also contributes to the rotational movement of the forearm and wrist (pronation and supination) and acts as a secondary bony stabiliser for the medial ligaments (ligaments on the inside of the elbow).

Would you like to see a doctor?

Learn more

Ligaments at the Elbow

Stability at the elbow joint comes both from the bony congruency between the articular surfaces and from the ligaments that run on the inside and outside of the elbow. Ligaments join bones to each other. The joint is surrounded by a loose capsule and these ligaments are in fact thickenings in the capsule that run from the lower end of the humerus to the upper end of the ulna on the inside and outside of the elbow. They also surround the radial head to provide stability to that articulation. The medial ulnar collateral ligament runs on the inside of the elbow while the lateral ulnar collateral ligament (or radial collateral ligament) runs on the outside of the elbow. The annular ligament surrounds the radial head allowing its smooth rotation but also providing stability.

Muscles that cross the Elbow

The muscles and tendons that cross the joint power the movements of the elbow joint. Muscles attached to bones with tendons (while bones attached to bones with ligaments). Tendon is a tough, non-elastic soft tissue structure whereas the muscle is soft and can contract and relax causing movement.

As with most joints there is rarely a single muscle performing each movement. Muscles work in conjunction with each other and there is a great deal of overlap in function. For this reason, injury to a single muscle or tendon does not always cause major dysfunction and does not always require surgical repair.

Muscles that flex the elbow: The strong muscles that flex the elbow (bend it) are the biceps and brachialis muscles. These muscles lie in the front of the elbow. Although the biceps is a strong flexor of the elbow it also contributes a great deal to supination (twisting the forearm with the palm up). This is important for activities such as turning a screwdriver a key. The other muscles that cross the elbow joint also contribute to elbow flexion to a lesser degree. These include the muscles from the hand and wrist that flex the fingers and wrist.

Muscles that extend the elbow: The triceps muscle extends the elbow (straightens it) it has a strong thick tendon that attaches to the olecranon (point of the elbow at the back). During most day-to-day activities gravity contributes a great deal to elbow extension. The triceps is the main muscle that helps to straighten the elbow under load for activities such as pushing oneself out of the chair.

Rotation of the forearm: Rotation of the forearm turning the palm down is called pronation and turning the palm up is called supination. The rotational movement of the forearm takes place through joints between the radius and ulna at both the lower end (distal radio-ulna joint at the wrist) and at the upper end (radiocapitellar joint and proximal radio-ulna joint at the elbow). It relies not only on the movement at these joints but also on the smooth rotation of the forearm bones as they roll around each other; crossing over in pronation or lying parallel in supination. The muscles of the forearm that power these movements include the pronator teres and supinator as well as the biceps muscle.

Forearm muscles: Other important muscles around the elbow are the common flexor and common extensor muscles groups. These are the groups of muscles that either flex (bend) or extend (straighten) the wrist and fingers. They run the length of the forearm and join either on the inside of the elbow (flexor muscles) or the outside of the elbow (extensor muscles). The tendons of these muscles transmit a great deal of load to the bone and are prone to injury and repetitive overuse.

Nerves that cross the Elbow

The large nerves that give function and sensation to the hand cross the elbow joint. These nerves may be injured during trauma or affected by compression around the elbow joint. They may also be at risk during some surgical procedures around the elbow.

At the back of the elbow on the inside (posteromedially) runs the ulna nerve. This nerve is quite superficial and bumping it can result in a painful “electric-shock” like sensation which runs down into the little finger. This is the classic “funny bone”. Compression of this nerve behind the elbow causes pins and needles or numbness in the little finger (cubital tunnel syndrome). It is important for fine motor function in the hand and innervates most of the small muscles in the hand. It also provides sensation to the little finger and that side of the palm.

The radial nerve curls around the upper arm from the inside of the arm higher up, round the back of the middle of the humerus and then runs down the outside of the upper arm crossing the elbow in front of the outer part of the elbow. This nerve lies directly on the bone of the humerus and can be injured when the humerus is fractured. It can also be compressed in the muscles of the upper forearm (supinator muscle) causing a dull ache or pain which can be confused with tennis elbow. The radial nerve supplies the muscles that extend the wrist and fingers. It also supplies sensation to the back of the hand.

The median nerve crosses the elbow in the middle at the front of the elbow and is rarely a problem at this point but can be injured with dislocations and fractures around the elbow. It is the nerve implicated in carpal tunnel syndrome at the wrist. This nerve supplies the long muscles that flex the fingers and thumb. It also supplies sensation to the thumb, index and middle finger and that part of the palm.

Surgery procedure

Elbow Arthroscopy

Many surgical procedures done within the elbow joint can be performed with arthroscopy (keyhole surgery). This involves the insertion of a fibreoptic scope through a small thin metal tube into the elbow joint. This is done through incisions of between 0.5 and 1 cm in length. The number of incisions used depends on the type of surgery being performed. This is less invasive surgery and while it may decrease the risks involved with wound healing in larger incisions, the same operation is being performed inside the joint. This means that the recovery can still take some time. The advantage of this approach is that the entire elbow joint can be examined through the camera. Areas that might not be visible to open surgery are visible and unexpected problems may be identified and dealt with at the same time.

Indications for elbow arthroscopy

Tennis elbow release: a tennis elbow release may be done either through open surgery or through arthroscopic surgery. The advantage of the arthroscopic procedure is that it allows better visualisation of the entire elbow and may identify other pathology. There is a slightly higher risk of nerve injury with the arthroscopic procedure. There are also reports of a slightly higher failure rate with arthroscopic tennis elbow releases compared to open tennis elbow releases. For this reason, the majority of uncomplicated tennis elbow surgery is performed open. In cases where there is a doubt in the diagnosis or dual pathology your surgeon may suggest doing the procedure arthroscopically in order to deal with the other pathology at the same time.

Removal of loose bodies: some patients may develop loose bodies of cartilage or bone within the elbow joint. This can be as a result of previous injury, arthritis or other less common rheumatological conditions. This frequently results in “locking” or “catching” of the elbow. It can also be accompanied by significant pain and stiffness. Arthroscopic surgery is an excellent way of assessing the elbow joint and removing these loose bodies which cause the mechanical symptoms. This often results in a dramatic improvement in symptoms which is noticeable even within the first few days.

Elbow joint arthritis: arthritis of the elbow is relatively uncommon compared to arthritis seen in other joints, for example hips and knees. Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and arthritis following an injury (post traumatic arthritis) do however occur in the elbow. These conditions can often be dealt with very effectively through arthroscopic procedures. While the procedure may not undo the arthritic damage and the cartilage damage within the joint it can improve the range of motion and can improve the pain through removal of inflammatory tissue. During the arthroscopic procedure the entire elbow joint can be assessed and extra spurs of bone (which grow as a result of the arthritis) can be removed. The lining of the joint which may become very inflamed, generate pain and block movement can also be removed (synovectomy). This may slow the progress of the arthritis and in some cases delay the need for more major surgery such as elbow replacements.

Elbow stiffness: the elbow joint may become stiff for a number of reasons. This most commonly occurs after injury or surgery for fractures or dislocations. In severe cases extra bone may grow across the elbow joint (heterotopic ossification) preventing or movement. While each of these cases needs to be judged on its own merit, many of them can be managed with arthroscopic surgery. During these procedures the extra bone that blocks the movement can be respected and the scar tissue and thickened capsule (joint lining) can be excised. In severe cases open surgery may be better able to access the heterotopic ossification. The pros and cons of both arthroscopic and open surgery will be discussed with you by your surgeon prior to any procedure.

Osteochondral defects: an osteochondral defect is a discrete area of damage to the cartilage and underlying bone in the elbow. This most commonly occurs in adolescent patients and may be as a result of overuse of the elbow. In some cases there is no clearly defined cause for this. Not all osteochondral defects require surgery but if the fragment becomes loose or there are mechanical symptoms (“locking”, “catching” or stiffness) then arthroscopic surgery is a good way to remove the loose body and debride the joint. A joint debridement involves removal of any rough areas of cartilage, excess bone or inflammatory tissue which may limit movement will cause pain.

Procedure

During and elbow arthroscopy the patient usually lies on the unaffected side. The elbow being operated on is rested on a padded bolster to support the arm and allow easy access during the surgery. The procedure is done under a general anaesthetic and this may be accompanied by a regional block. A regional block is when local anaesthetic is injected around the nerves in the neck that supply the elbow. This is done under ultrasound guidance to minimise the risk of nerve injury during this part of the procedure. The block allows the anaesthetist to use a lighter general anaesthetic and allows the patient to wake up pain free. It sometimes lasts as long as 24 hours and during this time the arm may be completely dead (this is normal) which can be a disconcerting feeling.

With the patient asleep an inflatable tourniquet is applied to the upper arm. This is inflated during the procedure to a controlled pressure which prevents blood from flowing into the surgical field. This allows better visualisation and more precise surgery. The pressure is carefully controlled but there are reports of neurological injury as a result of uncontrolled pressure. This is an extremely uncommon complication.

For elbow arthroscopy patients come in on the morning of the surgery and depending on the extent of the procedure may either stay overnight or potentially go home on the same day.

Post-operative care

After the surgery patients will be prescribed anti-inflammatories and painkillers. These should be started before the nerve block wears off and should be continued for at least the first 3 to 5 days as prescribed. As the pain improves the painkillers can be gradually stopped but care should be taken not to discontinue or pain medication to suddenly. This can result in rebound pain which may be more difficult to control. All patients experience pain differently and while some patients may discontinue the pain medication and anti-inflammatories early others will require pain medication for up to 6 weeks and sometimes longer. This is also dependent on the indications for the surgery

Patients will generally wake up with a thick, padded bandage around the elbow. This provides support and also restricts movement. In some cases, an additional sling will be placed on the arm for comfort. The amount of movement allowed after the surgery is dependent on the type of surgery done. Procedures which require healing of tendons or ligaments may need protected range of motion for a longer period of time (up to 6 weeks). For many other procedures including elbow debridement for arthritis and removal of loose bodies it is desirable to get the elbow moving as soon as possible. Your surgeon will confirm your post-operative mobilisation plan with you after the operation.